I have a love/hate relationship with tables. I love when we can incorporate any type of visual into CEL publications, but I hate to see poorly designed or unnecessary tables in academic writing. When creating a table, you have to make sure that it’s the right fit for the content (rather than just including a table because you can or think you should). In this post, I’ll go through some brief guidelines for creating effective tables. And I’ll share sources for those who need a deeper dive!

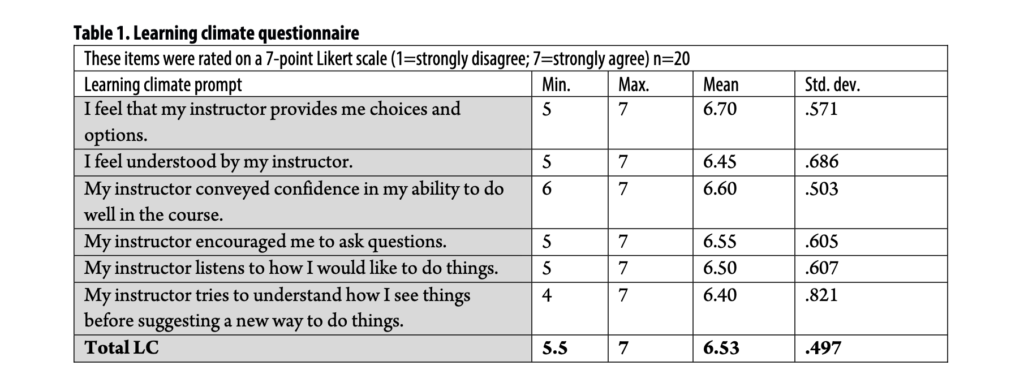

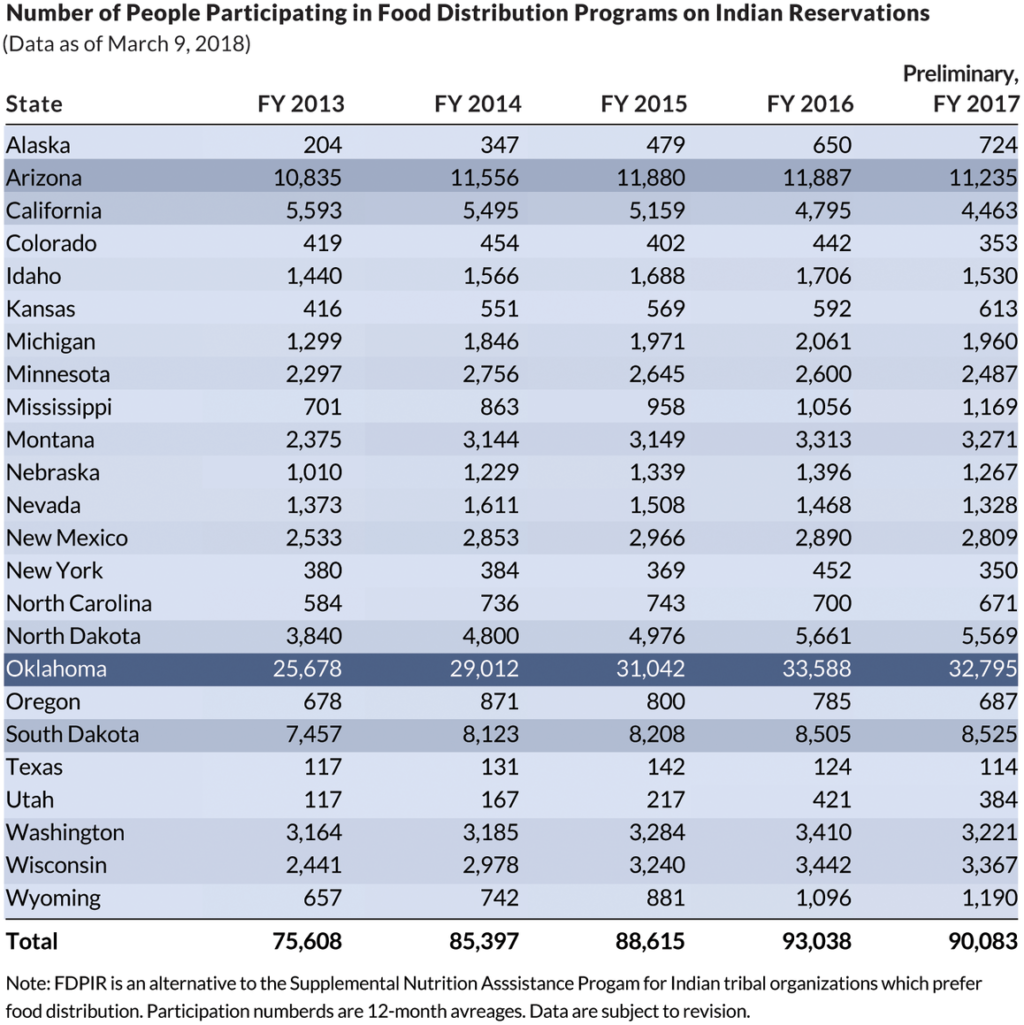

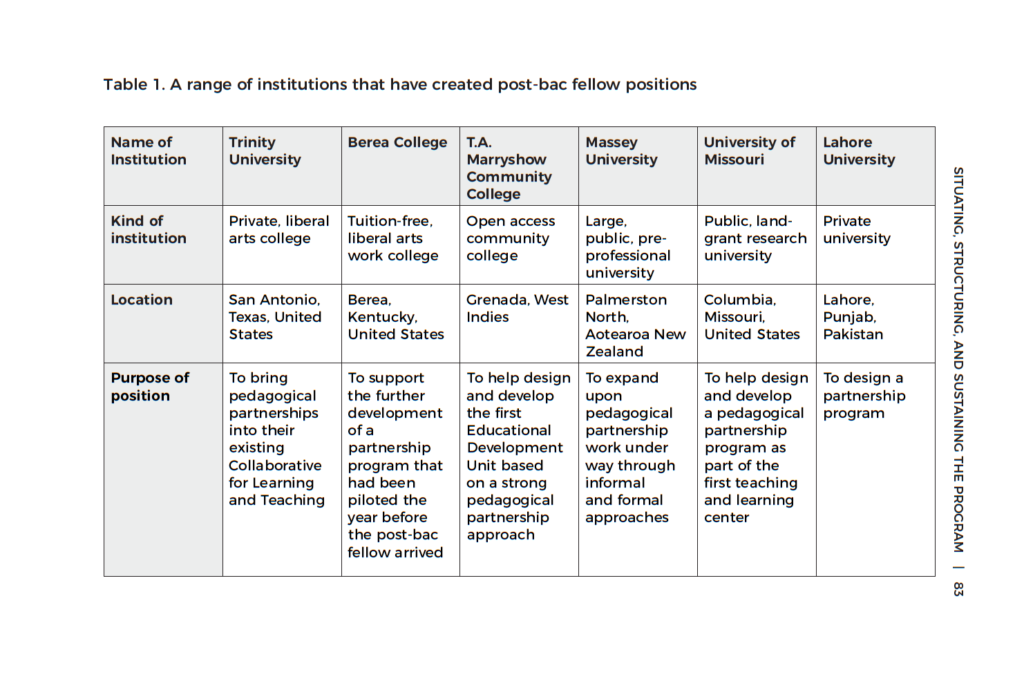

First think about what purpose the table is meant to serve for the reader. APA says, “Although tables and figures attract attention, they should not be used for mere decoration in an academic paper. Instead, every table and figure should serve a purpose” (195). It’s sometimes difficult to decide between a table, a chart (or other type of visualization), or a simple list. The Chicago Manual of Style says, “A table offers an excellent means of presenting a large number of individual, similar facts so that they are easy to scan and compare. A simple table can give information that would require several paragraphs to present textually, and it can do so more clearly” (148). Tables are usually the best choice when you want your readers to see the exact values (rather than, for example, data points on a chart).

Ideally each “table ‘tells’ a worthwhile and intelligible story” (Einsohn and Schwartz 2019, 247). How does your table support your argument? Do you want your readers to notice a particular pattern in your data? Should they notice an outlier? Or maybe you want to present a list of information, clearly organized so that readers can easily locate the individual fact(s) that they are interested in (a classic example is the old-fashioned telephone book).

Ask a colleague or critical friend to look at your table and tell you what meaning they get from it. If they don’t get what you’d like them to understand from it, either you don’t need a table (and the information would be clearer simply discussed in the text) or you need to change the information included in the table.

If you decide that your table is not absolutely necessary for most readers (though helpful for a subset who may be interested in seeing or using all your data), you might consider posting it online. For every CEL book, we have online supplemental resources that extend readers’ understanding and use of the books’ ideas — an ideal place for extra tables.

When creating a table that will appear in a book, remember that the trim size of your book will limit the size of your table. For a 6”x9” book, you will only have about 4.5” of horizontal space to fit in all your columns. For a landscape table, you will have limited height.

Your table should be as simple as possible, so that it fits nicely onto the page but also to lessen the strain on your readers’ cognitive load. Include only the data you need to make your argument. Write headings with clear, simple language. Use color and lines/dividers sparingly. Jonathan A. Schwabish has a great list of ten guidelines for formatting tables effectively.

Some readers will certainly read your table before (or even instead of) reading your text, so you have to make sure it makes sense out of context. “A table should be as simple as the material allows and understandable on its own; even a reader unfamiliar with the material presented should be able to make general sense of a table” (Chicago Manual Of Style, 148). Always include a title, and make it easy to read and understand. A note can be included below the table to provide any necessary explanation.

The main text should highlight the most important points of the table and give a sense of the data’s significance, but make sure you don’t duplicate the table’s content in text form. This explanation usually is unnecessary and lengthens your text. In your manuscript, avoid writing “in the table below” or “in the table on page 32” or anything similar — in the typesetting stage, tables will move around based on what layout will work best. Number your tables and use those numbers to refer to tables in the text.

And finally, if your book will be available for on-screen reading (as an e-book or PDF), your tables must not be images, but rather correctly marked-up text. This mark-up allows people using screen reading software to access the content. Contact your publisher to make sure this is happening, so that every reader can appreciate your well-designed and effective tables.

This post is an installment of our series on academic book publishing. If you missed any of the other posts, check them out:

APA (American Psychological Association). 2020. Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association: The Official Guide to APA Style. 7th edition. Washington, DC: APA.

Chicago Manual of Style. 2017. 17th edition. University of Chicago Press.

Einsohn, Amy, and Marilyn Schwartz. 2019. The Copyeditor’s Handbook: A Guide for Book Publishing and Corporate Communications. 4th edition. Oakland, CA: University of California Press.

Schwabish, Jonathan A. 2020. “Ten Guidelines for Better Tables.” Journal of Benefit-Cost Analysis 11 (2): 151-178. https://doi.org/10.1017/bca.2020.11.

Jennie Goforth is the Center for Engaged Learning’s Managing Editor. She works with authors to shepherd their work from proposal through production in the Center’s Open Access Book Series. She also manages production of book websites and supplemental materials for the Stylus Publishing/Center for Engaged Learning Series on Engaged Learning and Teaching.